by Casey Berna, MSW

Structural racism and implicit bias permeates many institutions throughout America, devastating the lives of African Americans. Healthcare, made of the medical institutions that reign under its umbrella, is no exception. The field of gynecology has an especially egregious history of horrific crimes of racial nature. The proclaimed “father of gynecology,” Dr. J. Marion Sims, performed torturous experiments on enslaved Black women without their consent, or anesthesia. The failure for doctors to acknowledge the humanity of African American women, and its appalling impact on patients, can still be seen today.

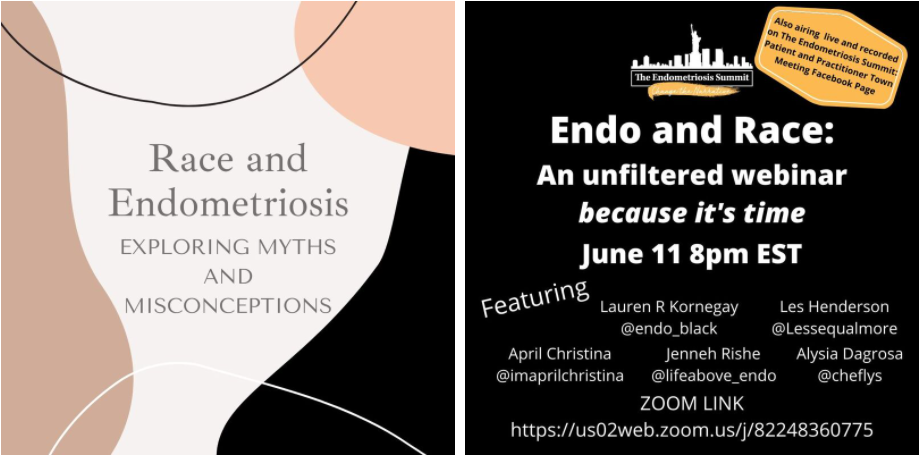

Recently, the Endometriosis Summit hosted two important discussions surrounding the challenges that African American endometriosis and infertility patients are confronted with due to racism and racial prejudices throughout healthcare. Advocates, Jenneh, Les, Alysia, Lauren, April, Kat, Claudia, and Dr. Thornton discuss the many harmful racist beliefs impacting care, open up about their personal experiences, while also sharing the incredible ways that they are making a difference and changing the narrative.

Myth #1: African Americans rarely get endometriosis.

While there are many myths that delay diagnosis and treatment, it seems wise to start with the most obvious one that is delaying care. Reproductive Endocrinologist, Dr. Melvin Thorton, explains that, “in textbooks physicians are taught that endometriosis is very rare in African Americans. Your average physician has that knowledge and they say, “Oh, it can’t be endometriosis because it is very rare in African American women and they miss the diagnosis and patients suffer going years and years without a diagnosis.” It took 18 years for Kat Haagenson, creator of Femme Power Health Blog, to get a diagnosis despite sharing early on with her doctors, “You know, my sister has endometriosis, maybe it could be this?” In June, endometriosis advocate Kyla Canzater called out Johns Hopkins Medicine for listing being white as a risk factor for having endometriosis. The lack of inclusion of African Americans in the endometriosis space is what led Lauren Kornegay to start her own organization, Endo Black, “When I started doing research, I was not able to find any research in reference to African American women or women of color who struggled or had endometriosis.”

Myth #2: African Americans are more likely to have painful periods and little can be done

Endometriosis advocate April Christina of @iamaprilchristina, lamented that she spent almost twenty years suffering and misdiagnosed, “because I am an African American woman, and because I am 3x more likely to have fibroids, there was nothing they could do…as if this is the known quality of life as an African American woman you have to go through…Until I saw an endometriosis expert, I didn’t realize there was way much more happening in my body than I knew.” Advocate Claudia Campbell, @endofierce, also had a dramatic delay in diagnosis due to the fact that doctors told her that her pain was normal, “I was told that as a Black woman…I was going to have painful periods for my entire life. Essentially, I was told this was going to be my story until menopause.”

Myth #3: Pelvic pain must be Pelvic Inflammatory Disease if you are African American.

While there should be no shame or stigma associated with having a sexually transmitted infection, being tested for one without consent and then being misdiagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease, leading to a delay in endometriosis diagnosis and treatment, is harmful to patients. Dr. Thornton unfortunately sees this happen frequently to African American patients who present with pelvic pain, “from a medical perspective, particularly for African American women…many women go to the emergency room or go to their private care doctors because of the pelvic pain, and the number one diagnosis they get is pelvic inflammatory disease.” Dr. Thornton warns that this misdiagnosis can follow patients for life. When patients see their fertility doctor years later, and the doctor asks them if they have ever had a pelvic infection, they say yes and then “the treatment and diagnosis goes towards a different direction, instead of the treatment of endometriosis.” Lauren laments that African American patients, “are treated off of these stereotypes that you really don’t have control over. Sometimes in the Black community it’s best to stay at home if you are not going to get the care that you need, if you are going to judge me, if you are going to look at me, and make assumptions about me.”

Myth #4: African Americans are not as sensitive to pain as white people.

This myth is perhaps the most disturbing and harmful. In 2016, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that half of white medical trainees believe African Americans have thicker skin or less sensitive nerve endings than white people. The pain that can come with endometriosis can be quite extreme, rather traumatizing, and frightening for patients who have experienced it.

Spending a lifetime of being undertreated for pain has impacted April’s health immensely and she dreads going to the doctor for treatment for her pain as she often leaves feeling worse. She explains, “If I am coming to you and I already have a 6 out of 10, by the time I am done with you, from you not even understanding or trying to comprehend or communicate with me, I’m already at an 11 out of 10.” Kat feels that racist stereotypes played a part in her not receiving the pain treatment she needed, “the strong Black woman stereotype…was pushed on me…a lot..(the idea that)I should be able to manage this pain and suppress my symptoms without…any interventions. Never did I ever receive any prescription medication to help with pain. Nothing. It was only, “You just manage it! You’re going to do fine! You got this! You are strong!””

Claudia has often been dismissed and labeled as she sought to get answers and treatment for her pain. She explains, “when I would be complaining about pain and…try to push back or get assertive in my care, I would get labeled as “the angry Black woman”…when I was upset that I wasn’t being heard I would hear maybe what I needed to do is go and see a psychiatrist because…it is all in my head.”

Myth #5: African Americans who are in pain are really just drug seekers.

Jenneh Bockari, is a nurse, endometriosis advocate, and founder of The Endometriosis Coalition. While working on a post-surgical trauma unit, she witnessed first hand how racism played into the treatment of pain, “I noticed that the label drug seeker was almost always placed on the African American patients and not on the Caucasian patients…to the point where I saw people withhold medications with the attitude, “I’m not going to feed their drug habit. I am not going to watch someone become an addict.”” Claudia experienced this label herself when seeking urgent treatment for pain, “I have been in the emergency room before where I have been labeled as a drug seeker.” Lauren reminds patients that, “We cannot continue to allow people that we are paying to not pay attention to our pain. A lot of women have been turned away…because they say they are going to abuse the drugs, even if you don’t have a…history of drug abuse! It is not their job to judge us, it is their job to assist us. It shouldn’t matter what I look like, what I am wearing, you should be coming there to assist me.”

Myth #6: African Americans are very fertile, yet, their fertility is not a priority.

When advocate Alysia complained of pelvic pain at just 19 years old, the options presented to her were to “go on birth control or get a hysterectomy.” Alysia also points out research shows the disparities in health when comparing the outcomes of Black women and white women. Black women are twice as likely to have a hysterectomy for benign conditions than white women. They are also more likely to have a hysterectomy at an earlier age, and have surgery via open laparotomy as opposed to laparoscopically. Les Henderson, founder of Endo Queer, a support, education, and advocacy group for LGTBQIA+ individuals with endometriosis, was told by her doctor, “Unless, you are going to switch teams, you really don’t need to come here,” and in response to her pain she was told, “You are not going to use your parts anyway, just get yourself gutted out. Just get a hysterectomy.” Dr Thornton explains, “A lot of African American women don’t seek treatment just because they have been frustrated and they were turned away from doctors and say I am not going to see another doctor because they are going to treat me the same way.”

Kat struggled for years without a diagnosis, “When I recently got my endometriosis diagnosis and I lost an ovary, it was a lot of grief and frustration. I felt like if I had been listened to when I was younger, all of this could have been prevented. I could have kept my ovary. I could have had better chances with fertility and facing the things that I am facing now at 35…Furthermore, no one told me about seeking a fertility specialist. It was all, you should be fine! Maybe it was your husband? No one ever wanted to do any extra testing on me or refer me out to a fertility specialist.” Kat felt ignored and dismissed, “I felt like no one took my questions about my infertility and about my desire to start my family seriously.”

Dr. Thornton confirmed that it is very common for African American women not to get a referral to a fertility specialist. Claudia kept hearing that she shouldn’t have a problem getting pregnant. She felt, “the general myth or misconception that Black women are very fertile alone, did create a barrier from an access perspective…it took me quite some time before I went to a fertility specialist because my doctor wouldn’t refer me…because Black women are fertile.” And when Claudia and her husband eventually connected with a specialist, the lack of African Americans in the information sessions, in the waiting rooms of the office, in the marketing materials, and in the pictures hanging up on the walls in the office made her feel more isolated. She expresses, “All of that contributes to the shame as well because somewhere along the line you feel like as a Black woman, I should be able to do this. Everybody else must be doing this…I want Black women, Black couples, to be able to get into the fertility specialist earlier…We shouldn’t be waiting 18 months, 24 months and really having to advocate for our own selves and hunting down a RE on our own.”

Myth #7: All care is created equal.

Health disparities due to systemic racism and implicit bias impact many African American endometriosis and infertility patients. While wealth does not erase the impact racism has on care, where you live, what type of insurance you have, and how much you have in savings to afford endometriosis and infertility specialists do have a big impact on quality of care. Les talks about how there is a “big difference in care between not having insurance, to being on medicaid, to having private insurance.” Lauren stresses that, “when you live in a certain neighborhood, you are already classified to a certain hospital. If you do not have transportation, if you are not able to access resources, you are not able to get transported to one of the best hospitals in that town.” Some small, rural towns may not always even have an ob gyn on staff at their hospital, never mind a provider who is educated and equipped to treat complex endometriosis. Jenneh feels that, “it took me way too long, as someone who has a lot of medical knowledge and background to figure out what was going on with me I couldn’t imagine what it was like for people who do not have my wealth of knowledge.”

Infertility treatments can also be cost prohibitive, with only some states mandating coverage for patients. Dr. Thornton believes that, “Infertility is a disease. We have to come to that and treat it as any other disease. Patients should have full coverage.” When it came to infertility costs, Kat feels, “There was just a barrier to entry when it came to cost…So I kind of disqualified myself because I was afraid to even go there.”

Myth #8: There is no racism in healthcare.

Dr. Thornton admits, “these stories make me very sad, because they are the same stories I heard 30 years ago and they haven’t changed. We can try and educate physicians as much as we can, but patients need to be active. The system is set up for women not to be heard.” Indeed, such a long history of abuse from medical institutions and their providers creates an understandable mistrust from patients, which hinders diagnosis and treatment of serious, life-altering disease. Lauren points out, “Going back to experimentation, those are things that unfortunately did happen to African American people…we have a clear distrust across the board of the medical community. It is very difficult for us to break that when we are going to the hospital and we are not getting the treatment or we are not getting the attention or even getting listened to.”

Claudia wants healthcare providers to know that, “Endometriosis in Black women is real. There is a phrase, we are strong Black women, and that is very true, but strong women feel pain. We need to be heard and be understood…We want you to understand us, we want you to listen to us and we want you to treat us. That is all we ever wanted.” Les feels that, “If a doctor took me seriously early on, maybe I wouldn’t be dealing with the things I am dealing now.”

What to do to change the narrative:

Jenneh urges other advocates and non-profits in the community to remember that, “there is a large population of people just like us. Put faces to these people. Keep us in mind when you are coming up with initiatives and coming up with plans…I don’t think the endo space is reflected to be as diverse as it actually is.” Claudia implores providers that, “If your patients are having painful periods, if your patient is undergoing symptoms of something, you’re treating a symptom of something. It is very likely your patient may have trouble conceiving, in that case, it shouldn’t be when your patient is 30-35 that you are having these conversations.” Les, who has created an important space for not only African American patients, but for those that are in the LGTBQIA+ community, another group that is often marginalized, encourages patients to, “Keep telling your story. If you are silent no one will know. Closed mouths don’t get fed.” She also encourages medical providers, institutions and those who hold power over policies that need to be transformed to, “Really listen to this and take it back to medical practices, or wherever you are. Really mean it and take this back. Really listen to what each and everyone is saying and take this back into your offices, take it back to your practices and put it into your research.”

To listen to the entirety of these conversations, hosted by The Endometriosis Summit please check out the below links:

Endometriosis and Race

Endometriosis, Race, and Fertility

To learn more about Anti-Racist and Trauma Informed Patient Care please join the Pelvic Guru’s team (@pelvicguru1 on Instagram) for this incredible webinar https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0A7NjsgaZVg&t=12s

Follow and support these African American advocates and their organizations:

April Christina

Lauren Kornegay @ Endo Black

Alysia

Samantha Denae

Les Henderson @ Endo Queer

Jenneh Riche Bockari at The Endometriosis Coalition

Claudia Campbell @Endofierce

Kat Haagenson at FemmePower Health Blog

Though not featured in this article, also make sure to check out the Sister Girl Foundation and

The Millen Magese Foundation.

The Kegel Room podcast with Lotus Pelvic Physical Therapy

Also, please mark October 25th on your calendars for the Reproductive Immunology Summit where we will be exploring Stigma and Infertility and Pregnancy Loss.

Save the Date for EndoSummit 2021: One Voice which will be held worldwide virtually March 6-7 2021.

To volunteer with the endometriosis summit please email: [email protected]